The Revolutionary Responses of Locke and Sidney

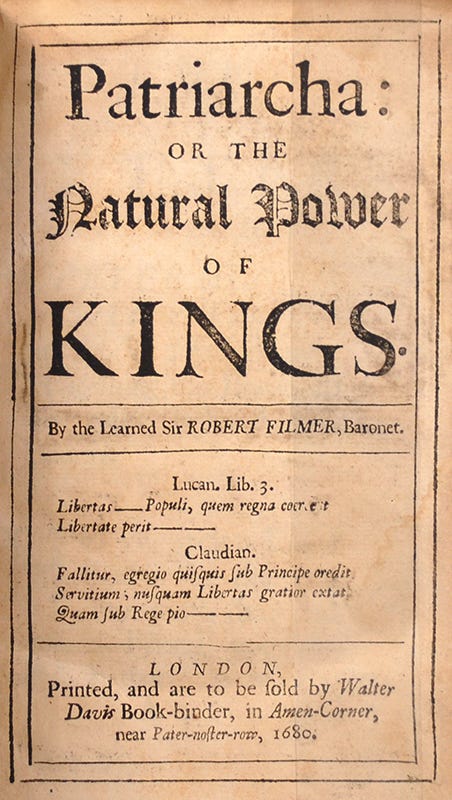

Both John Locke's "Two Treatises of Government" and Algernon Sidney's "Discourses Concerning Government" were rebuttals to Robert Filmer's "Patriarcha: or The Natural Power of Kings".

In 17th-century England, Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha: or The Natural Power of Kings (written 1635–1642, published 1680) stood as a cornerstone of the establishment’s defense of absolute monarchy. This treatise argued that political power stemmed from divine right and patriarchal authority, tracing back to Adam. Filmer’s ideas justified unchecked monarchical power, portraying rebellion as sinful.

However, John Locke and Algernon Sidney boldly challenged this view in Two Treatises of Government (1689) and Discourses Concerning Government (written 1679–1683, published 1698). Their rebuttals sparked controversy in their time and laid the ideological foundation for America’s Founding Fathers a century later, shaping the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Patriarcha: or The Natural Power of Kings

Filmer’s Patriarcha emerged during England’s political upheavals, including the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the Restoration of Charles II (1660). It provided a robust defense of the divine right of kings, aligning with royalist sentiments. Key points of Filmer’s thesis include:

Divine and Patriarchal Authority: Filmer claimed kings derived absolute power from God’s grant to Adam, passed through paternal lines, making monarchy a natural, divine order.

Obedience Over Liberty: Subjects owed unconditional loyalty to rulers, akin to children obeying parents, with no inherent rights to liberty or consent.

Biblical Foundation: Filmer relied on selective biblical interpretations, particularly from Genesis, to argue that hierarchical rule was God-ordained.

This framework comforted royalists by sanctifying monarchy and dismissing notions of popular sovereignty, portraying opposition as heretical.

Two Treatises of Government

John Locke (1632–1704), a physician and Enlightenment philosopher, directly confronted Filmer in his First Treatise of Government. He dismantled the patriarchal model and, in his Second Treatise, proposed a government based on reason and consent. Locke’s key arguments were:

Natural Rights: Individuals are born free and equal, possessing inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property, not granted by rulers.

Social Contract: Government authority arises from a voluntary agreement among individuals, revocable if rulers violate citizens’ rights.

Right to Revolution: People may overthrow oppressive governments that breach the social contract.

Limited Government: Power should be divided across branches to prevent tyranny and ensure accountability.

Locke’s ideas were radical in the 1680s, challenging James II’s absolutist regime. Published anonymously to avoid persecution, his work risked treason charges but gained traction during the Glorious Revolution (1688), which deposed James II.

Discourses Concerning Government

Algernon Sidney (1623–1683), a soldier and republican, refuted Filmer in Discourses Concerning Government. His passionate defense of liberty and resistance made him a martyr after his 1683 execution under Charles II. Sidney’s core ideas included:

Government by Consent: Political power stems from the people, not divine or hereditary mandate, forming a contract to protect liberty.

Right to Revolution: Citizens have a natural right to resist tyrannical rulers, grounded in natural law.

Civic Virtue: Liberty requires active citizen participation to prevent corruption and despotism.

Mixed Government: Drawing from classical republicanism, Sidney advocated for balanced governance with checks on power.

Sidney’s manuscript was used as evidence in his treason trial, highlighting the danger of his ideas. His execution amplified his influence, casting him as a symbol of resistance.

Locke and Sidney’s rebuttals were provocative in a society recovering from civil war and fearing anarchy. Their challenge to Filmer’s divine hierarchy threatened the established order by:

Empowering the People: Suggesting authority was conditional and revocable gave ordinary citizens power to judge rulers.

Clashing with Absolutism: Locke’s rational approach and Sidney’s republicanism opposed religious and monarchical absolutism.

Risking Persecution: Both wrote in secrecy or exile, with Sidney’s execution underscoring the peril of dissent.

Their ideas gained legitimacy during the Glorious Revolution, but critics branded them seditious, as they evoked fears of regicide (the killing of a king) and instability.

Founding Influences

By the 1760s, colonial grievances against British rule, including taxation without representation and arbitrary laws, mirrored England’s earlier struggles. The Founding Fathers turned to Locke and Sidney for intellectual support:

Declaration of Independence (1776): Thomas Jefferson adapted Locke’s natural rights, proclaiming “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as inalienable. The document echoed both thinkers’ views on consent and the right to revolution.

U.S. Constitution (1787): James Madison incorporated Lockean separation of powers and Sidney’s balanced government, with the preamble emphasizing popular sovereignty.

Jefferson recommended both Two Treatises and Discourses for study. John Adams praised Locke and Sidney as philosophers of liberty in 1775 and 1787 writings. Benjamin Franklin’s library included Sidney’s works, and his motto “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God” reflected Sidney’s spirit.

Locke and Sidney’s triumph over Filmer’s absolutism shaped America’s political foundation. Locke provided a systematic framework for rights and governance, while Sidney’s radical rhetoric and martyrdom galvanized revolutionary action. Their ideas transformed controversy into a constitutional republic, emphasizing liberty over hierarchy. Today, their principles of consent, rights, and resistance remain central to American governance, proving that challenging the establishment can forge enduring freedoms.